The story of the Shining Path begins in the shadow of the Andes, where jagged peaks pierce the sky and and silence blankets the valleys like a heavy fog. It was here, in the late 1960s, that Abimael Guzmán, a philosophy professor, revolutionary, and future architect of terror, decided Peru needed to be destroyed to be saved.

I remember reading and watching documentaries about Guzmán some years ago, I got stuck in a Wikipedia loop about the communist guerillas. He went by "Chairman Gonzalo," like he was some kind of messiah or honorable man. He wasn't. He was a man who believed in Maoism so deeply that he thought rural Peruvians, those who barely had electricity, would rise up and fight for his vision of a communist utopia. And when they didn't? He forced them.

In 1980, while the rest of Peru was preparing for democratic elections, Guzmán was preparing for war. His "Shining Path" started small, burning ballot boxes in remote Ayacucho villages, but escalated fast. Villages that resisted were taught harsh lessons. Women were tortured. Men were executed. They didn’t just kill; they destroyed. Churches, schools, community centers, all gone. This wasn’t liberation. This was submission.

But the Shining Path wasn't just fighting villagers. They declared war on the government, blowing up buildings in Lima and assassinating anyone they deemed a "class enemy." One of their most infamous moments came in 1992 when they bombed the wealthy Miraflores district in Lima, killing 25 people. They wanted to prove that no one, not even the elite, was safe. And they succeeded. People were terrified.

Their ideology wasn’t just Maoism, it was absolute, unrelenting control. Guzmán’s version of Maoism didn’t have room for traditional cultures or local beliefs. Ironically, the very indigenous communities he claimed to fight for were often his first victims. If villagers prayed at a church or refused to join his revolution, they were branded counter-revolutionaries. They called it a "cleansing." To me, it just sounds like genocide.

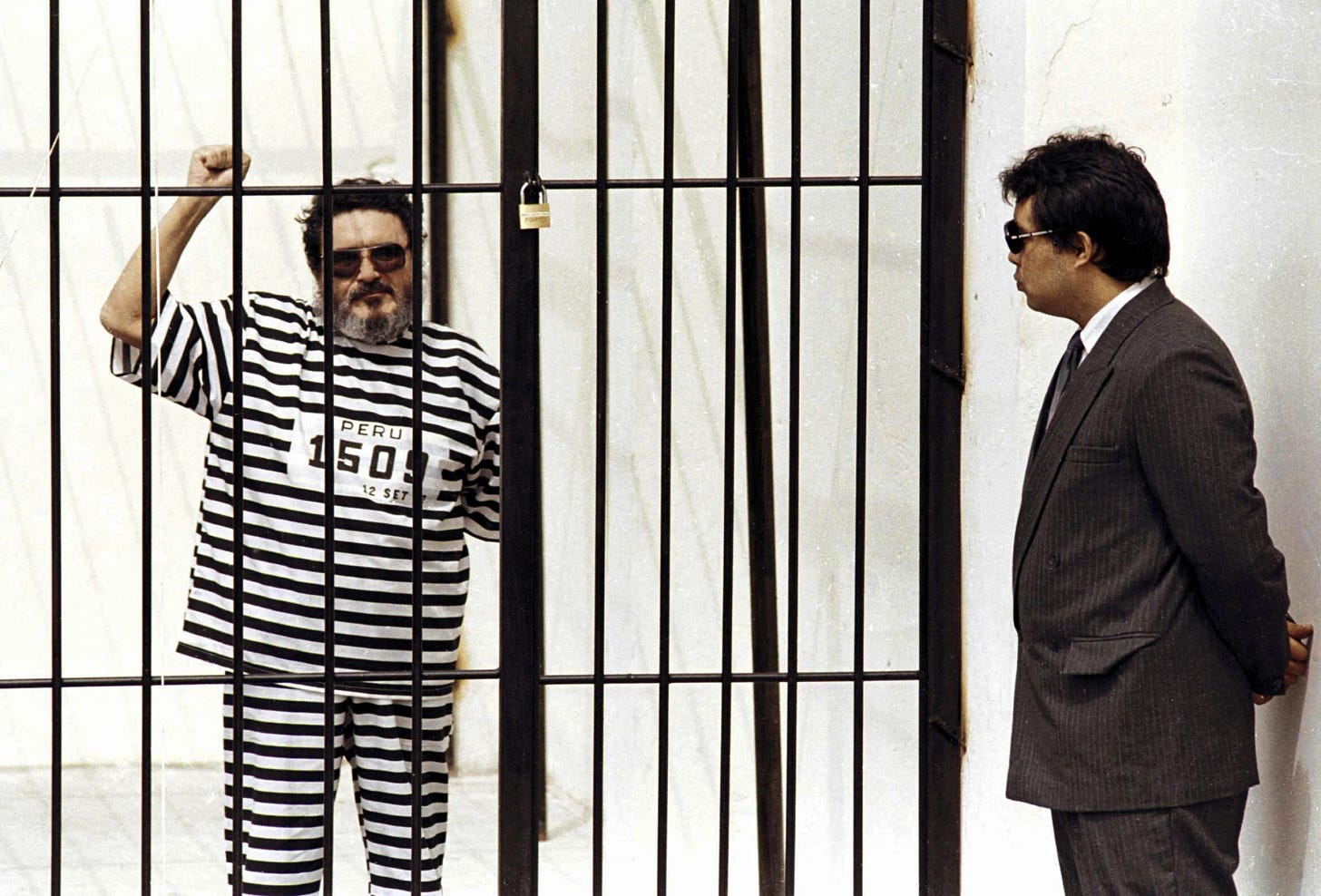

But Guzmán overplayed his hand. By the early '90s, Peru had had enough. The government ramped up its counterinsurgency efforts, deploying military forces to track him down. In September 1992, they finally got him. Guzmán was arrested in Lima, shown to the world in a striped prison jumpsuit, caged like an animal. That image became a symbol of his downfall. His capture marked the beginning of the end for the Shining Path.

You’d think that would’ve been it, a chapter closed. But no. Even after Guzmán was sentenced to life in prison, the Shining Path didn’t completely die. A faction of them retreated deep into the jungle, into the lawless region known as the VRAEM (Valley of the Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro Rivers). And there, they reinvented themselves, not as revolutionaries but as drug traffickers.

Cocaine. That’s what keeps them alive today. They tax coca farmers, protect drug shipments, and make deals with cartels. It’s almost laughable. The Shining Path started out claiming to fight imperialism, capitalism, and exploitation. Now they’re just another piece of the global drug trade, a cartel pretending to be a revolution.

It’s strange to think about where this all started. Guzmán wanted to bring utopia to the people, but he brought them hell instead. Tens of thousands of people died during the insurgency, and even now, the scars haven’t healed. If you travel to those remote villages in Ayacucho, you’ll still find survivors, old men and women who remember the terror, the fear, the silence that followed when the Shining Path came to town.

The Shining Path isn’t what it was, but it’s not gone either. And maybe that’s the hardest part. You can capture a man like Guzmán, you can kill his movement, but the ideology? The chaos? That lingers.